Images and Idols.

To Find More Interesting Resources Click below :

|

On several occasions during my travels through all parts of India, I asked intelligent Paṇḍits how they could reconcile the gross idolatry and fetish-worship which meet the eye at almost every step throughout the length and breadth of their land, with the doctrine repeatedly declared to be the only true creed of Brāhmanism—the doctrine that nothing really exists but the one eternal, omnipresent Spirit of the Universe (named Brahman or Brahmă)[244].

The answer I generally received to this inquiry was, that spiritual worship was at first the only form of religion dominant in India, till the Buddhists set the example of worshipping material objects and images (pratimā-pūjā).

Of course it is impossible to say what amount of truth there may be in this accusation. It seems probable that material impersonations of the forces of nature existed before the Buddha’s time. Yet there is no evidence of the prevalence of actual idolatry at the time when the Ṛig-veda was composed. Nor is there any very clear allusion to it in Manu. Nor have any images of Hindū gods been found which are 466 so ancient as some Buddhist images. At the same time nothing is said about image-worship in the Buddhist Piṭakas. The statement that the Buddha himself sanctioned idolatry is wholly legendary (see p. 177). Nor is there any proof that carved images of his person were common in India till several centuries after his death.

The Bharhut sculptures of about the second century B.C.—though representing many scenes connected with the Buddha (see pp. 408, 523)—exhibit no representations of the Buddha himself. Nor are there any on the Sānchī gateway of still later date.

The only objects of reverence in the Bharhut sculptures, according to Sir A. Cunningham, are Bodhi-trees, Wheels, the Tri-ratna symbol, Stūpas, and foot-prints (see pp. 521-522 of these Lectures). The bas-reliefs on the railing at the Buddha-Gayā Temple, which is of a little earlier date, agree in making the Tree, Wheel, Tri-ratna, and Stūpa the great objects of reverence. On the other hand, in the edicts of king Aṡoka veneration for the Bodhi-tree alone is enjoined. Among the historical scenes represented in the Bharhut sculptures, are the processions of the kings Ajāta-ṡatru and Prasenajit on their visits to the Buddha; ‘the former on his elephant, the latter in his chariot, exactly as they are described in the Buddhist chronicles.’ There are also bas-reliefs which seem to represent Rāma, during his exile, besides images of other gods, Yakshas and Nāgas, but no figure of Buddha himself is to be seen anywhere.

Yet it is undeniable that in the early centuries of our era, images of Gautama Buddha and other Buddhas and Bodhi-sattvas had become common among the Buddhists in every part of India.

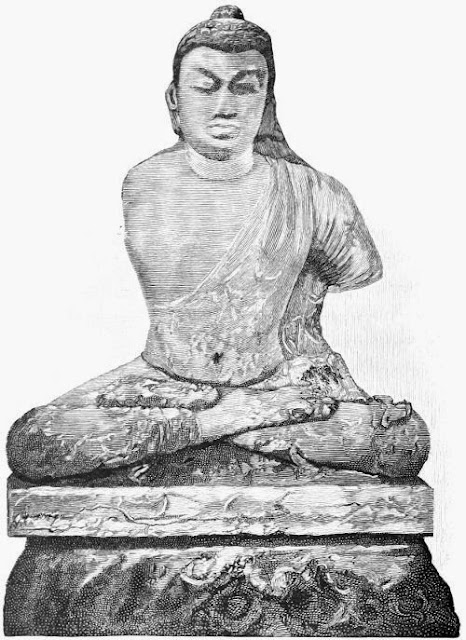

REMAINS OF A COLOSSAL STATUE OF BUDDHA, PROBABLY ONCE IN THE ARGUMENTATIVE OR TEACHING ATTITUDE.

Found in the ruins close to the south side of the Buddha-Gayā temple, the date (S. 64 = A.D. 142) being inscribed on the pedestal. (see p. 481)

467

One of the oldest statues of the Buddha that has yet been brought to light is the colossal image (now in the Calcutta Museum) dug up in the ruins outside the ancient temple at Buddha-Gayā (p. 390), the date inscribed on which corresponds to about A.D. 142. The engraving (opposite) is from a photograph of this statue, belonging to Sir A. Cunningham[245]. The thick lips are certainly remarkable. The attitude was probably the ‘argumentative’ or ‘teaching’ (described at p. 481). Another colossal statue of about the same date was found by Sir A. Cunningham at Ṡrāvastī (see p. 408).

It was indeed by a strange irony of fate that the man who denied any god or any being higher than himself, and told his followers to look to themselves alone for salvation, should have been not only deified and worshipped, but represented by more images than any other being ever idolized in any part of the world. In fact images, statues, statuettes, carvings in bas-relief, paintings, and representations of him in all attitudes are absolutely innumerable. In caves, monasteries, and temples, on Dāgabas, votive Stūpas, monuments and rocks, they are multiplied infinitely and in endless variety, and not only are isolated images manufactured out of all kinds of materials, but rows on rows are sculptured in relief, and the greater the number the 468 greater religious merit accrues to the sculptor, and—if they are dedicated at sacred places—to the dedicator also.

And not only images of the Buddha, but representations of every object that could possibly be connected with him, became multiplied to an indefinite extent.

The gradual growth of what may be called objective Buddhism, and the steps which led to every kind of extravagance in the idolatrous use of images, may be described in the following manner:—

It was only natural that the disciples of an ideally perfect man, who had taught them that in passing away at death he would become absolutely extinct, should have devised some method of perpetuating his memory and stimulating a desire to conform to his example. Their first method was to preserve the relics of his burnt body, and to honour every object associated with his earthly career. Then, in process of time, they began to worship not only his relics but the receptacles under which they were buried, and around these they placed sculptures commemorative of his life and teaching. Thence they passed on to the carving or moulding of small statuettes of his person in wood, stone, metal, terra-cotta, or clay, and on these they often inscribed the well-known Buddhistic formulæ mentioned before (see p. 104). Eventually, too, painting was pressed into the service, and frescoes on walls became common. Indeed in some temples paintings take the place of images, as objects of adoration.

It seems likely that the use of images and paintings was at first confined to the brotherhood, and it is 469 alleged that they were only honoured and not worshipped. But the more the circle of uncultured and unthinking Buddhists became enlarged, the more did visible representations of the founder of Buddhism become needed, and the more they became multiplied.

Nor was this all. The reaction from the original simplicity of Buddhism led to a complete repudiation of its anti-theistic doctrines. It adopted polytheistic superstitions even more rapidly and thoroughly than Brāhmanism did. People were not satisfied with representations of the founder of Buddhism. They craved for other visible and tangible objects of adoration—for the images of other Buddhas and Bodhi-sattvas—of gods many and lords many—insomuch that a Buddhist Pantheon was gradually created which became peopled with a more motley crowd of occupants than that of Brāhmanism and Hindūism.

Furthermore, it was only natural that the manufacture of the whole array of divinities and semi-divinities, of saints and sages, should have been committed to the monks. They alone possessed this privilege. They alone, too, had the power of consecrating each image by the repetition of mystical texts and formularies. And when images and idols were thus consecrated, they were believed to be animated with the spirit, and to possess all the attributes of the beings they represented.

In fact, the development of every phase of idolatrous superstition reached a point of extravagance unparalleled in any other religious system of the world. The monks of Buddhism vied with each other in the ‘pious 470 fraud’ with which they constructed their idols. They so manipulated them that they appeared to give out light or to flash supernatural glances from their crystal eyes. Or they made them deliver oracular utterances, or they furnished them with movable limbs, so that a head would unexpectedly nod, or a hand be raised to bless the worshipper. Then they clothed them with costly vestments, and adorned them with ornaments and jewels, and treated them in every way as if they were living energizing personalities.

It ought, however, to be noted here, that in some temples images of the Buddhas and Bodhi-sattvas were said to exist which were not manufactured or consecrated by monks. They were believed to have been self-produced, or to have been created supernaturally out of nothing, or to have emerged in a miraculous manner out of vacuity. The child-like faith of uncultured and imaginative races in the virtue supposed to be inherent in such images was perhaps not surprising. The power of working all kinds of miracles was gradually ascribed to them; sicknesses were said to be healed by them, rain to be produced, and the course of nature itself to be subject to their direction and control.

The two Chinese pilgrims Fā-hien and Hiouen Thsang are never tired of describing the wonders supposed to have been wrought by the statues and idols they saw during their travels, especially by the marvellous sandal-wood statue mentioned before (see p. 408).

The following tradition in regard to this image, narrated by Fā-hien (Legge, 56, 57), is especially interesting as showing that the general belief among all 471 classes of Buddhists in his time was, that Gautama Buddha himself was the first to sanction the making of visible representations of himself:—

When Buddha went up to the Trayastriṉṡa heaven and preached the law for the benefit of his mother for ninety days, Prasenajit longing to see him, caused an image to be carved in Goṡīrsha sandal-wood, and put in the place where he usually sat. When Buddha, on his return, entered the Vihāra, this image immediately left its place, and came forth to meet him. Buddha then said to it: ‘Return to your seat. After I have attained Pari-nirvāṇa you shall serve as a pattern to the four classes (paths, see p. 132) of my disciples.’ Thereupon the image returned to its seat. This was the very first of all the images of Buddha, and that which men subsequently copied.

In Hiouen Thsang’s narrative, which is of much later date (see p. 413), we find the following account of this celebrated sandal-wood image (Beal, ii. 322):—

To Find More Interesting Resources Click below :

|

At the town of Pimā (Pi-mo) there is a figure of Buddha in a standing position made of sandal-wood. The figure is about twenty feet high. It works many miracles, and reflects constantly a bright light. Those who have any disease, according to the part affected, cover the corresponding place on the statue with gold-leaf, and forthwith they are healed. People who address prayers to it, with a sincere heart, mostly obtain their wishes. This is what the natives say: ‘This image in old days, when Buddha was alive, was made by Udayana, King of Kauṡāmbī (see p. 412 of these Lectures). When Buddha left the world, it mounted of its own accord into the air, and came to the north of this kingdom to the town of Ho-lo-lo-kia (Urgha?).’

With regard to the form and character of the countless images now scattered everywhere, they vary according to country and period (see p. 485). It should be observed, however, that Buddhism, when it began to encourage idolatry, did not make it hideous by giving monstrous shapes to its idols. In this respect early Buddhism contrasted very favourably with Hindūism. 472 Nor did the Buddhists of India, as of other countries, adopt the practice of endowing their idols with extra heads and arms to symbolize power, or of inventing grotesque combinations of the human figure with the shapes of elephants, birds, serpents, and other animals. They seemed rather to have tried in the first instance to neutralize the tendency to extravagant symbolism common among all Eastern peoples, by delineating their great teacher as an ideal man, simply and naturally formed, according to the Buddhist ideal of perfection with symmetrical limbs, and a dignified, calm, passionless, and majestic bearing. What can be a greater contrast than the four-armed elephant-headed village-god of India,—Gaṇeṡa, son of Ṡiva[246]—and the purely human figure of the Buddha as shown in his statues!

Nevertheless it must be admitted that in process of time the representations of Gautama Buddha developed certain peculiar varieties of form as well as differences in attitude. These differences, indeed, constitute a highly interesting topic of inquiry, and perhaps deserve more attention than they have hitherto received in any treatise with which I am acquainted.

Without going minutely into every point, we may begin by noting a few general characteristics common to all the Buddha’s images.

In the first place, they all represent Gautama as clothed—not naked. In this respect they present a pleasant contrast to the images of Jaina saints; for, as 473 already pointed out, Gautama discountenanced all extremes of bodily mortification, and disapproved the practice of going about nude, according to the custom of Hindū devotees. In the Dharma-pada it is said, ‘Not nakedness, not matted hair, not dirt, not fasting, nor lying on the ground, nor smearing with ashes, nor sitting motionless can purify a mortal who has not overcome desires.’

Gautama’s robe was drawn gracefully over his shoulders like a toga, but probably the right shoulder was always left bare on formal occasions. The Piṭakas give no clear information as to this point. In Indian statues the robe is sometimes represented as fitting so closely to the body that the figure seems garmentless[247]; its presence being merely denoted by a line running diagonally over the left shoulder across the breast, and under the right arm. This line frequently looks so like a cord that some have mistaken it for the thread to which, as a Kshatriya, Buddha was entitled[248]. In some ancient images no trace of the line is left, but they are not really nude. Most Indian images have the right shoulder bare (even in the case of nuns). Of course in colder climates both shoulders are covered. Even in Southern countries some have both shoulders covered, or the right partially so.

In contradistinction to the clothed images of the Buddha, all the representations of his great opponent 474 and rival Deva-datta (see pp. 52, 405) make the latter unclothed, like a Jaina ascetic, or only partially clothed up to the waist. Deva-datta is also represented as shorter in stature than the Buddha.

Other characteristics generally to be observed in the earlier images of Gautama Buddha are:—the impassive tranquil features, typical of complete conquest over the passions, and of perfect repose; the absence of all decoration and ornament; the long pendulous ears, which occasionally reach to the shoulders[249]; the circle or small globe or lotus[250], or auspicious mark of some kind, on the palm or palms of the supinated hands (as well as often on the soles of the feet), and the short knobby hair, often carved so as to resemble a close-fitting curly wig.

It must not be forgotten that Gautama signalized his renunciation of the world by cutting off his hair with a sword, and the resulting stumps are said to have turned into permanent knobs or short curls[251].

In images brought from Burma and Siam a curious horn-like protuberance on the crown of the head—either tapering to a point, or rounded off at the extremity—is 475 noticeable. Often, too, sculptures found in India show the rounded form of this excrescence.

Some think that it represents an ascetic’s mass of hair coiled up in a top-knot on the crown of the head, as in images of the god Ṡiva. Others regard it as the rough outline of what ought to be an Ushṇīsha or peculiar crown-like head-dress, such as may be seen in many later images of the Buddha. Some legends declare that the Buddha was born with this Ushṇīsha, which was indicative of his future supremacy.

Others, again, maintain that this protuberance (sometimes lengthened out so as to be as high as the head itself) was a peculiar growth of the skull, and one of the marks of a supreme Buddha indicative of supernatural intelligence; just as in other images (especially those brought from Ceylon) five flames—in shape like the fingers of a hand—are represented issuing from the crown of the head (see p. 453), to typify the Buddha’s diffusion of light and knowledge throughout the world.

It is said that this outgrowth of the Buddha’s skull has been preserved as a sacred relic in a town of Afghānistān near Jalālābād.

In many representations of the Buddha, a Nimbus or aureola of glory encircles the head (see p. 478), and in some images rays of light are represented as emerging from his whole body. An image with a halo of this kind surrounding the entire figure was seen by me in a temple near Kandy in Ceylon (see p. 453).

In Nepāl many images represent Buddha holding his alms-bowl, but these are not common in other places.

With regard to the size of the images, they vary 476 from diminutive examples, two or three inches long, to colossal statues twelve, eighteen, twenty, thirty, forty, or even seventy feet high. They are generally carved in stone or marble, but sometimes in metal, sometimes in wood, and occasionally moulded in clay.

Much difference of opinion prevails as to the Buddha’s actual stature. When I asked the opinion of Buddhist teachers in Ceylon, they all agreed in assigning to the founder of their religion a majestic bodily frame, not only gifting him with the possession of the thirty-two distinguishing marks of a perfect man and supreme Buddha (see p. 20), but with great height and imposing presence. A common idea is that the eighteen-feet statues represent life-size. According to other legends the Buddha’s stature reached to twenty cubits. In China, the mythical history of Buddha gives him a height of only sixteen feet[252]. His arms are by some said to have been so long, that he was able to touch his knees with his hands without stooping, and if we are to take the supposed impress of his foot on Adam’s Peak and in Siam as the measure of his stature, he must have been the most gigantic giant that ever lived. Even one of the most enlightened natives of Ceylon, the late Mr. James d’Alwis—a convert to Christianity—told me, in explanation of the abnormal size of the eye-tooth at Kandy, that he was convinced that all human beings were taller in Buddha’s time, and that Gautama was taller than his fellow-men of those days, and was about eight feet high. It was his opinion that as sin increases in the world, so men’s stature decreases. Probably the Buddha was tall, even for the North-west of India, where the average of a man’s stature is about five feet eight or nine inches.

SCULPTURE FOUND BY SIR A. CUNNINGHAM AT SĀRNĀTH, NEAR BENARES,

Illustrating the four principal events in Gautama Buddha’s life—his birth from his mother’s side, his attainment of Buddhahood under the tree, his teaching at Benares, and his passing away in complete Nirvāṇa. (Date of the sculpture, about 400 A.D.)

477

As to the attitudes of Gautama’s images, they may be classed under the three heads of sedent, erect, and recumbent. I use the word ‘sedent’ for what ought to be called a squatting position, with the legs folded under the body. Images which represent a figure sitting in European fashion are rare.

Four principal images represent the four principal events in Buddha’s life, as shown in the Sārnāth sculpture engraved on the opposite page (compare p. 387).

The first sedent attitude may be called the ‘Meditative.’ The example below is described at p. xxx.

This represents the Buddha seated, in meditation, on a raised seat under the sacred tree, with the two hands supinated, one over the other.

The second sedent attitude may be called the ‘Witness-attitude.’ It is perhaps the most esteemed of all, and is represented in a good sculpture delineated below (from Sir A. Cunningham’s photograph, see p. xxx. 17). This represents Gautama at the moment of achieving Buddhahood after his long course of meditation, seated on a lion-throne (siṉhāsana) with an ornamental back, having two lions carved below (compare p. 394). His legs are folded in the usual Indian fashion, the feet being turned upwards, while the right hand hangs over the right leg and points to the earth, and the left hand is supinated on the left foot. He 479 has an aureola round his head and a mark—perhaps the caste-mark of a Kshatriya—on his forehead, and an umbrella over the sacred tree. This attitude is well shown in the Sārnāth sculpture (facing p. 477).

The tradition is that at the moment of his enlightenment Gautama was taunted by the evil being Māra with being unable to give any proof or sign of his Buddhahood. Thereupon Gautama pointed, not to heaven as a Brāhman might have done, but to the earth beneath his feet, calling it to witness. Then a six-fold earthquake and other miraculous phenomena followed[253].

At this time, too, the evil being Māra sent his enchanting daughters (p. 34) to seduce the Buddha. This is shown in the engraving facing p. 477.

The incident of calling the earth to witness is thus mentioned by Hiouen Thsang:—

In the Vihāra, was found a beautiful figure of Buddha in a sitting position, the right foot uppermost, the left hand resting, the right hand hanging down. He was sitting facing the east, and as dignified in appearance as when alive. The signs and marks of a Buddha were perfectly drawn. The loving expression of his face was like life. Now it happened that a Ṡramaṇa, who was passing the night in the Vihāra, had a dream, in which he saw a Brāhman who said:—

‘I am Maitreya Bodhi-sattva. Fearing that the mind of no artist could conceive the beauty of the sacred features, I myself have come to delineate the figure of Buddha. His right hand hangs down, in token that when he was about to reach Buddhahood the evil Māra came to tempt him, saying, “Who will bear witness for you?” Then Tathāgata dropped his hand and pointed to the ground, saying, “Here is my witness.” On this an earth-spirit leapt forth to bear witness.’ (Beal’s Records, ii. 121, abridged.)

This ‘Witness-attitude’ is also shown in the annexed 480 engraving from a photograph of one of the only statues that remained in the exterior niches of the ancient Buddha-Gayā temple before its restoration.

The two seal-like circles on each side contain the usual ‘Ye dharmā’ formula (see p. 104 and p. xxx. 18).

The third sedent pose or position may be called the ‘Serpent-canopied.’ This is commemorative of the legend that Gautama, when seated in meditation after his attainment of Buddhahood, was sheltered from a violent storm by the expanded hood of the Nāga, or serpent-demon Mućalinda (see p. 39), while the coils of the snake were wound round his body, or gathered under him to form a seat. Similarly the ascetic form of Ṡiva is often represented under a serpent-canopy.

481

Only one example of this has been found at Buddha-Gayā. Such images, however, are common in the south, and their prevalence there is not difficult to account for. Indeed, the connexion of Buddhism with the serpent-worship of southern countries and with the Nāgas of Hindū mythology (see p. 220 of these Lectures), was one inevitable result of its readiness to graft popular superstitions on its own doctrines[254].

I procured a good specimen of the ‘Serpent-canopied’ Buddha during my stay in Ceylon. It is made of heavy brass, and curiously enough represents Buddha with an aquiline nose. It has the five rays of light before alluded to (see pp. 453, 475) issuing from the crown of his head. See the frontispiece opposite title-page.

In some images an umbrella alone, and in some, as at p. 478, both an umbrella and tree form the canopy.

The fourth sedent posture may be called the ‘Argumentative’ (Tarka) attitude (as shown in the engraving opposite p. 477). It represents Gautama with the thumb and finger of the right hand touching the fingers of the left, and apparently going through the heads of his doctrine[255], and enforcing it, as he usually did, by reiterations. This is sometimes called the ‘Teaching’ attitude.

Often the ‘Ye dharmā’ formula (see p. 104) is carved either under or at the side of images in this attitude.

482

The fifth may be called the ‘Preaching’ attitude. It is often erect. The Buddha has one finger raised in a didactic manner. Monks in the present day often read the Law and preach in the same manner.

The sixth attitude also—as a rule—comes under the erect class, and is often scarcely to be distinguished from the last. It may be called the ‘Benedictive’ attitude (Āṡirvāda). See the engraving opposite p. 477.

It represents the Buddha in the act of pronouncing a benediction, the right hand being raised. This attitude is sometimes sedent. Even to this day Buddhist monks bless laymen in a similar attitude. Occasionally the figure with the hand upraised has a crown, and an ornamental head-dress; but it may be taken for granted that all images of the Buddha which represent him with a crown of any kind after his attainment of Buddhahood, are comparatively modern and incorrect.

On the other hand, it is clear that even ancient sculptures, when they represent him as a prince, may correctly give him decorations and a head-dress.

The seventh attitude may be called the ‘Mendicant.’ This also is a standing figure, holding a round alms-bowl in one hand, and sometimes screening it with the other (compare p. 40). Examples of this attitude are rare. There are no real mendicants in Buddhism. No monk ever begs, he only receives alms.

The eighth and last attitude is recumbent, and this is perhaps as important as the second, though not so common (see the uppermost figure opposite to p. 477). It represents the moribund Gautama lying down on his right side, with his head turned towards the north, 483 and his right cheek resting on his right hand, about to pass away in the final consummation of Pari-nirvāṇa (see pp. 50, 140). In many representations of this attitude, the usual five rays of light often mentioned before are made to issue from the crown of the head. A colossal image of this kind was seen by me in a temple near Colombo, and there is a good example of it in the Indian Institute at Oxford[256]. In some carvings of the dying Buddha a few attendants are represented, who hold umbrella-like canopies over the recumbent figure, or bow down reverentially before it. It has been asserted that this scene—as commemorative of the grand consummation of the Buddha’s career through countless existences—is held in as much reverence by Buddhists as the crucifixion is by Christians.

The representation of the Buddha in the act of being born is found in sculptures and bas-reliefs, but is never found as a separate image. It represents him springing out of the side of his mother (note, p. 180). This birth-scene is occasionally carved on temples. It is shown in the lower part of the engraving (opposite page 477). The god Brahmā is seen receiving the new-born child, while Indra stands on his right and the mother’s sister (i.e. nurse, p. 24) is on her left.

Some representations of the Buddha, or of certain forms of the Buddha—such as Amitābha—show a sedent figure emerging from a lotus-blossom, or seated on a pedestal formed of lotus-leaves, this flower symbolizing perfection.

484

It must not be forgotten that in every country the images of the Buddha are generally moulded according to the type of countenance prevalent in each country. Hence the contour and expression of face differ in Ceylon, Burma, Siam, Tibet, Mongolia, China, and Japan, although as a rule the features are calm, mild, meditative, and passionless.

In Burma the people are merry; hence the images sometimes have a twinkle in the eye and smiling lips.

In China, again, examples sometimes occur of images which do not exhibit Buddha as the ideal of a man who has conquered his passions, but rather with the figure and features of a self-indulgent libertine[257]; while others again portray him with a grim aspect.

We now pass on to the representations of other Buddhas, Bodhi-sattvas, saints, gods and goddesses.

Often two other images are associated with that of Gautama Buddha himself.

And, first of all, his image was joined with the other two persons of the earliest Triad (see p. 175), viz. Dharma (the Law) and Saṅgha (the Monkhood). A sculpture, in a broken and imperfect condition, representing this earliest Triad, and dating from the ninth to the tenth century, was found at Buddha-Gayā. The image of Buddha, under an umbrella-like tree, is in the centre; that of the Saṅgha is on his right, with a full-blown 485 lotus (p. 177, note 2), and having one leg hanging down, while that of Dharma (a female) is on his left with a half-blown lotus. A drawing of this (from Sir A. Cunningham’s photograph) is given below:—

Next come the images of the Buddhas who preceded Gautama, especially Kāṡyapa Buddha, Kanaka-muni, and Kraku-ććhanda. It is often mentioned that the images of one or other of these three, as of the Bodhi-sattvas, are set up side by side with that of Gautama.

Then, of course, there are the images of the five Dhyāni-Buddhas. Perhaps the commonest of these is that of Amitābha (see p. 203), but images of Akshobhya and Ratna-sambhava are by no means rare.

Then as to the Bodhi-sattvas, of whom Maitreya is the first and the only one worshipped by Buddhists of 486 all countries (see p. 182), Fā-hien records that he saw in Northern India a wooden image of Maitreya Bodhi-sattva eighty cubits high, which on fast days emitted a brilliant light. Offerings were constantly presented to it by the kings of surrounding countries (Legge, 23).

Hiouen Thsang (Beal, i. 134) also describes this image of Maitreya as very dazzling, and says it was the work of the Arhat Madhyāntika, a disciple of Ānanda. He saw another image of Maitreya made of silver at Buddha-Gayā, and another made of sandal-wood in Western India. The latter also gave out a bright light. Probably these images were covered with some kind of gilding.

In the present day the images of Maitreya often represent him with both hands raised, the fingers forming the lotus-shaped Mudrā, the body yellow or gilded, and the hair short and curly.

Passing next to the images of the triad of mythical Bodhi-sattvas, Mañju-ṡrī, Avalokiteṡvara, and Vajra-pāṇi (p. 195), we may gather from what has been already stated (p. 196), that the interaction of Buddhism and Hindūism affected both the mythology and imagery of both systems. Yet it does not appear that the images of the Bodhi-sattva Mañju-ṡrī were ever unnaturally distorted. They are quite as human and pleasant in appearance as those of Gautama and Maitreya. In general Mañju-ṡrī represented in a sedent attitude, with his left hand holding a lotus, and his right holding the sword of wisdom, with a shining blade to dissipate the darkness of ignorance (see p. 201). His body ought to be yellow.

487

It was not till the introduction of the worship of Avalokiteṡvara that the followers of Buddha thought of endowing the figures of deified saints with an extra number of heads and arms.

The process of Avalokiteṡvara’s (Padma-pāṇi’s) creation and the formation of his numerous heads by the Dhyāni-Buddha Amitābha, is thus described (Schlagintweit, p. 84, abridged):—

Once upon a time Amitābha, after giving himself up to earnest meditation, caused a red ray of light to issue from his right eye, which brought Padma-pāṇi Bodhi-sattva into existence; while from his left eye burst forth a blue ray of light, which becoming incarnate in the two wives of King Srong Tsan (see p. 271), had power to enlighten the minds of human beings. Amitābha then blessed Padma-pāṇi’s Bodhi-sattva by laying his hands upon him, so that by virtue of this benediction, he brought forth the prayer ‘Om maṇi padme Hūm.’ Padma-pāṇi then made a solemn vow to rescue all the beings in hell from their pains, saying to himself:—‘If I fail, may my head split into a thousand pieces!’ After remaining absorbed in contemplation for some time, he proceeded to the various hells, expecting to find that the inhabitants, through the efficacy of his meditations, had ascended to the higher worlds. And this indeed he found they had done. But no sooner was their release accomplished than all the hells again became as full as ever, the places of the out-going tenants being supplied by an equal number of new-comers. This so astounded the unhappy Bodhi-sattva that his head instantly split into a thousand pieces. Then Amitābha, deeply moved by his son’s misfortune, hastened to his assistance, and formed the thousand pieces into ten heads.

Schlagintweit states, and I have myself observed, that Avalokiteṡvara’s eleven heads are generally represented as forming a pyramid, and are ranged in four rows. Each series of heads has a particular complexion. The three faces resting on the neck are white, the 488 three above yellow, the next three red, the tenth blue, and the eleventh—that is, the head of his father Amitābha at the top of all[258]—is red. In Japanese images the heads are much smaller, and are arranged like a crown, the centre of which is formed by two entire figures, the lower one sitting, the other standing above it. Ten small heads are combined with these two figures.

The number of Avalokiteṡvara’s hands ought to amount to a thousand, and he is called ‘a thousand-eyed,’ as having the eye of wisdom on each palm. Of course all these thousand arms and eyes cannot be represented in images. Still there is an idol in the British Museum which represents him with about forty arms, two of which have the hands joined in an attitude of worship.

A remarkable description of an image of Avalokiteṡvara seen by Sarat Chandra Dās (so recently as 1882) in the great temple at Lhāssa occurs in his ‘Narrative’ (which I here abridge):—

Next to the image of Buddha, the most conspicuous figure was that of Chanrassig (i. e. the eleven-faced Avalokiteṡvara). The origin of this is ascribed to King Sron Tsan Gampo (p. 271 of this volume). Once the king heard a voice from heaven, saying that if he constructed an image of Avalokiteṡvara of the size of his own person, all his desires would be fulfilled.

Thereupon he proceeded to do so, and the materials he used were a branch of the sacred Bodhi-tree, a portion of the Vajrāsana, some soil from an oceanic island, some sand from the river Nairañjana, some pith of Goṡīrsha sandal-wood, a portion of the soil of the eight sacred 489 places of ancient India, and many other rare articles pounded together and made into paste, with the milk of a red cow and a she-goat. This paste the king touched with his head, and prayed to the all-knowing Buddhas and the host of Bodhi-sattvas, that by the merit of making that image, there might be god-speed to the great work he had undertaken—namely, the diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet.

The gods, Buddhas, saints, etc. filled the aerial space to listen to his prayer.

The king then ordered the Nepālese artist to hasten the completion of the image, and with a view of heightening its sanctity, obtained a sandal-wood image of Avalokiteṡvara from Ceylon and inserted it inside, together with the relics of the seven past Buddhas. When the work was finished, the artist said:—

‘Sire, I cannot say that I have made this image, it has passed into self-grown existence.’ Then a current of lightning flashed forth from its feet. Afterwards, the souls of the king and his queen are said to have been absorbed into it, in consequence of which this image is called ‘the five-absorbed self-sprung.’

It is recorded in another tradition that a wonder-working image of Avalokiteṡvara was set up in a monastery near Kabul, and another in Magadha near the Ganges. Any worshipper who approached these idols in devotion and faith were favoured with a personal vision of the saint. The statues opened, and the Bodhi-sattva emerged in bright rays of light (compare Koeppen, i. p. 499).

Originally, and still in Tibet, Avalokiteṡvara (otherwise called Padma-pāṇi) had only male attributes; but in China this deity (as we have already mentioned at p. 200) is represented as a woman, called Kwan-yin (in Japan Kwan-non), with a thousand arms and a thousand eyes. She has her principal seat in the island of Poo-too, on the coast of China, which is a place of pilgrimage.

490

There are two images of Kwan-yin in the British Museum, one with sixteen arms and the other with eight.

Images of the third mythical Bodhi-sattva—the fierce Vajra-pāṇi, ‘holding a thunderbolt in one hand’—like one form of Ṡiva—are almost as common as those of the merciful and mild Avalokiteṡvara. He has been described in a previous Lecture (p. 201).

In the Pitt-Rivers collection at Oxford there is an image of this Bodhi-sattva engaged in combating the power of evil. It is remarkable that the figures of three monkeys are carved underneath, one stopping his ears with his hands, another stopping his eyes, and another his mouth, to symbolize the effort to prevent the entrance of evil desires through the three most important organs of sense.

With regard to the images of female deities we may observe that Tārā, the wife or Ṡakti of Amogha-siddha (p. 216), is represented as a green sedent figure; her right hand on her knee, her left holding a lotus.

A standing image of the goddess Paṭṭinī (p. 217 of this volume) may be seen in the British Museum.

In a temple which I visited near Dārjīling I saw the image of the Padma-sambhava or ‘lotus-born’ form of Buddha occupying the centre of the altar, with the images of Gautama Buddha and of Buddha Āyushmat, or the ‘Buddha of Life,’ on each side.

Sir R. Temple (Journal, p. 212) relates how in a chamber of a Sikkim monastery there were three figures, the central of which, with a fair complexion, 491 was Amitābha, that on its right Gautama Buddha, and on its left Gorakh-nāth (see p. 193 of this volume).

In the monastery of Galdan (p. 441) Mr. Sarat Chandra Dās saw the golden image of Tsong Khapa (with his golden chain and his tooth and his block-prints), along with the images of Amitābha, Gautama, Maitreya, Bhairava (the awful defender of Buddhism), Yama ‘the lord of death,’ and his terrific messengers.

In the great Cho Khang at Lhāssa (see p. 459) he saw images of Avalokiteṡvara, Mañju-srī, Maitreya, Kuvera, Padma-sambhava, with an immense number of others, and especially one of the terrific goddess Paldan (or Pandan) who is feared all over Tibet, Mongolia, and China, as the greatest guardian deity of the Dalai and Tashi Lāmas and of the Buddhist Dharma. He found her shrine infested with mice, who are believed to be metamorphosed monks.

At Sera (p. 442) he saw images of the Buddha in his character of ‘demon-vanquisher,’ along with Maitreya (in silver), Avalokiteṡvara, the six-armed Bhairava, the goddess Kālī, Dolkar (= Tārā, p. 271), the Tāntrik Vajra-vārāhī, the sixteen Sthaviras (pp. 48, 255), and a great variety of others.

At Radeng (p. 273) he saw a golden image of Milaraspa (p. 384).

In the monastery of Sam ye (p. 448) he saw images of the Indian Paṇḍits who brought Buddhism into Tibet, with a vast number of other images.

At Tashi Lunpo he saw golden images of Buddha and Maitreya, besides images of 1000 other Buddhas (p. 189), and the four guardians of the quarters (p. 206).

492

At Yarlung he saw an image of Vairoćana Buddha, besides images of the sixteen Sthaviras, and a gigantic image of the king of the Nāgas, and a terrific representation of the demon Rāvaṇa (of the Rāmāyaṇa).

At Mindolling he saw fresco paintings of the six classes of beings (p. 122) inhabiting the six corresponding worlds. Of course delineations of the Jātakas (p. 111) and pictures of all kinds were common in monasteries and temples everywhere.

The two wonder-working images brought from Nepāl and China have been already mentioned (p. 271).

As an illustration of the monstrous superstition and idolatry prevalent in modern Buddhist countries, I venture, in conclusion, to quote, with abridgment, the following description of an idol seen by Miss Bird in Japan (see her ‘Unbeaten Tracks in Japan,’ published by Mr. Murray):—

In one shrine is a large idol spotted all over with pellets of paper, and hundreds of these may be seen sticking to the wire-netting which protects him. A worshipper writes his petition on paper, or, better still, has it written for him by the priest, chews it to a pulp and spits it at the divinity. If, having been well aimed, it passes through the wire and sticks, it is a good omen, if it lodges in the netting the prayer has probably been unheard.

On the left there is a shrine with a screen, to which innumerable prayers have been tied. On the right sits one of Buddha’s original sixteen disciples (see p. 47 of these Lectures). A Koolie with a swelled knee applied it to the knee of the idol, while one with inflamed eyelids rubbed his eyelids on it!

No comments:

Post a Comment